There's an odd thing about the last measure of Dvorak's 8th Symphony: no one plays. It's a bar of rest with a fermata over it, for the entire orchestra -- as if to tell the audience, "We'll wait, just clap whenever you feel like!" Of course, the audience won't get that message, unless they happen to be following along in the score. The conductor is not going to beat time for that measure, and the musicians don't have anything to do either, but damp their strings and wait for applause.

It seemed like a strange, sort of John Cage-ish thing for Dvorak to do, composing the silence after the music. Then I noticed today that Schubert's 9th Symphony also ends with a bar of rest, as do Schubert's 4th and 5th. So there must be some explanation - it can't have just been a slip of the pen. I wonder if something about the phrase structure dictated that bar be included - or if the orchestra would cut off that last note differently if it didn't have the empty space following it.

I really have no idea, and it's bugging me.

I like to think that perhaps Dvorak and Schubert just wanted to say, "Well, for the last hour or so, I've organized all the sonorities in this room - I've been controlling your aural experience. It doesn't take some famous dead guy to make sounds into music, though; ultimately what enters your ears, and reaches your mind and heart, is all up to you. Fill this empty measure with whatever sounds move you, or fill it with nothing at all - I leave the choice to you."

It's like when you leave an art museum, and walk out onto a city street. You've just been absorbing dozens of artists' visions of what is beautiful, but suddenly the only one that counts is your own. Which way do you look, what do you notice, how can you tilt your gaze to catch a passing glimmer - how do you frame your own experiences? That's what art asks each of us to decide, and it's a big question. You might need a long, grand pause to figure out a good answer.

Showing posts with label philosophy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label philosophy. Show all posts

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

making fun of philosophy

I can be sort of a hypocrite when it comes to reading. I'm always telling other people what to read, but then someone else recommends a book - like Brad and Denise, my friends here in Calgary who loaned me The Consolations of Philosophy by Alain de Botton - and I'm like stubborn old George W. Bush: I'll be the decider! Well, I listened to my friends' advice for once, and I'm so glad I did. This was one of those books that feels like it's been written specifically just for you, even if millions of other readers feel the same way too.

I can be sort of a hypocrite when it comes to reading. I'm always telling other people what to read, but then someone else recommends a book - like Brad and Denise, my friends here in Calgary who loaned me The Consolations of Philosophy by Alain de Botton - and I'm like stubborn old George W. Bush: I'll be the decider! Well, I listened to my friends' advice for once, and I'm so glad I did. This was one of those books that feels like it's been written specifically just for you, even if millions of other readers feel the same way too.Alain de Botton takes on some of the most-discussed and least-read thinkers in the Western canon: Socrates, Epicurus, Seneca, Montaigne, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. Before this all I'd read was a little bit of Nietzsche, which I found totally incomprehensible. It's hardly the fault of the philosophers themselves, though: their translators and publishers seem to like packaging their writing in books which practically seem to glower at you through the cover. If philosophy offers relief from suffering, you wonder, how come reading it causes suffering?

Consolations corrects the problem, with more laughs, anecdotes, and whimsical asides per page than any other philosophical text you're likely to read. And having obtained a copy, you are likely to read it, because it makes these ideas and the people producing them seem so lively and fun. De Botton seems to take a cue from the blogosphere, sticking in a silly picture or diagram whenever things threaten to get dull - yes, it's philosophy with pictures! - but it's hardly philosophy for dummies, and his imaginative, clever writing style insures against any dullness that might approach.

My favorite section of the book was on Montaigne - I actually might go out and find a copy of the Essays, I liked him so much. As de Botton writes:

[Montaigne] was concerned with the whole man, with the creation of an alternative to the portraits which had left out most of what man was. It was why his book came to include discussions of his meals, his penis, his stools, his sexual conquests and his farts - details which had seldom featured in a serious book before, so gravely did they flout man's image of himself as a rational creature.He sounds like a blogger living before his time.

- page 129

Wednesday, September 19, 2007

ancient wisdom on nerves

My limbs cannot hold me

And my mouth becomes dry

And trembling shakes my whole body

My hair all stands on end.

Gandiva falls from my hand

A fire runs under my skin

And I cannot stand still

My mind whirls as in flame

And, You of Fine Hair,

I see but omens of evil

Nor surely can good ever come

From killing my kinsmen in fight.

- from the Bhagavad Gita, 1.29-31, translated by Ann Stanford

That sounds quite a bit like some auditions I've taken. The rest of the Bhagavad Gita is largely about why Arjuna should overcome his nerves, go ahead and fight, even kill his friends and kinsmen if necessary - big philosophical arguments. But it's surprisingly relevant to anyone competing, auditioning, or just striving to do his or her best.

You have a right to the work alone

But never to its fruits.

Let not the fruits be your motive

Nor set your heart on doing nothing.

Steadfast in the Way, without attachment,

Do your work, Victorious One,

The same in success and misfortune.

This evenness -- that is discipline.

- same translation, 2.47-48

It's a great book, and a reminder that a warrior's struggles are timeless and shared by everyone, musicians included. And just a side note - the word translated as 'discipline' is actually 'yoga'. Its meaning has changed since the writing of the Gita (some time between 500-100BC), but it's still an extraordinary practice to discipline the mind.

Thursday, August 30, 2007

Heaven is a place on earth?

The things of earth are symbols of the things of Heaven: the sun corresponds to the deity. There is no time in Heaven. Things' appearances change to correspond to states of emotion; each Angel's clothing shines in proportion to its intelligence. In Heaven, the rich continue to be richer than the poor, since they are accustomed to wealth. In Heaven, objects, furniture, and cities are more concrete and complex than they are on our earth; colors are more varied and more vivid. Angels of English descent are drawn toward politics; Jews, to the jewel trade; Germans carry books about with them that they consult before answering a question. Since Muslims are in the habit of worshipping Mohammed, God has provided them with an Angel who pretends to be the Prophet. The pleasures of Paradise are withheld from the poor in spirit and all ascetics, because they would not understand them.

- Jorge Luis Borges, from "Swedenborg's Angels" in The Book of Imaginary Beings, p. 8-9

Borges is describing the theology of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), an English philosopher and scientist. What I love about his Heaven, apart from the complex furniture (and who doesn't want some more varied and vivid colors?) is the way it manages to accommodate everyone else's ideas of Heaven as well.

With so many different ideas floating around, you'd think someone is bound to be disillusioned and disappointed. Or even realize their whole belief system was flat-out wrong. Unless, of course, it's all been worked out so that people can keep their illusions, their presumptions, and maybe even their portfolios intact.

So maybe it's a big, jumbled, messy place with no fundamental truth that everyone can agree on - sort of like the pre-afterlife, actually. You didn't think you'd escape politics that easily, did you?

Wednesday, May 02, 2007

reflections upon the polished surface

I have my dead, and I have let them go,

and was amazed to see them so contented,

so soon at home in being dead, so cheerful,

so unlike their reputation. Only you

return; brush past me, loiter, try to knock

against something, so that the sound reveals

your presence. Oh don't take from me what I

am slowly learning. I'm sure you have gone astray

if you are moved to homesickness for anything

in this dimension. We transform these Things;

they aren't real, they are only the reflections

upon the polished surface of our being.

- Rilke, from "Requiem for a Friend"

I opened by book of Rilke's collected poems at random and started reading this one this evening. Almost immediately I had that sense of reading my own experiences and thoughts, only written much more beautifully. Lately more and more I feel like music is something that actually haunts us - some visitor from another dimension, perhaps, or a memory from another lifetime. In any case, it comes to us like a dream, but one so urgent it makes this waking life seem like the illusion.

Reading further into the poem, I realize it's a very deeply felt and personal message to a friend Rilke lost - perhaps it shows my peculiar obsessiveness that I most readily connect these sentiments to music, not to any actual person! Still, it strikes me as a very close analogy to my relationship to music - it can sometimes feel like a close friend whom I've lost, but who I knew so well that I am able to recreate her presence on some level. Maybe it doesn't happen all the time, maybe hardly ever, but in those rare moments when this lost person comes alive in me, it makes all the struggle worth doing.

My apologies to anyone who was hoping for the continuation of my audition story today. I seem to have gone all pensive and philosophical instead, but I promise to take it up again tomorrow!

Wednesday, April 11, 2007

renouncing renunciation

Asceticism, of course, is no solution: it is sensuality with a negative prefix. For a saint this might become useful, as a kind of scaffolding. At the intersection of his various acts of renunciation he beholds that god of opposition, the god of the invisible who has not yet created anything. But anyone who has committed to using his senses in order to grasp appearances as pure and forms as true on earth: how could such an individual even begin to distance himself from anything! And even if such renunciations proved initially helpful and necessary for him, in his case it would be nothing more than a deception, a ruse, a scheme - and ultimately it would take its revenge somewhere in the contours of his finished work by showing up there as an undue hardness, aridity, barrenness, and cowardice.Even though I draw inspiration from these words, I can't say I've exactly lived up to them. For most of my life, I've been renouncing one thing or another: television, drinking, the beach, relationships, blogging... It sometimes seems like every recreation, every source of pleasure I have discovered in life has had to be weighed against my greatest pleasure and purpose, which is making music. And in most cases I have limited, or even renounced altogether, those non-musical pleasures.

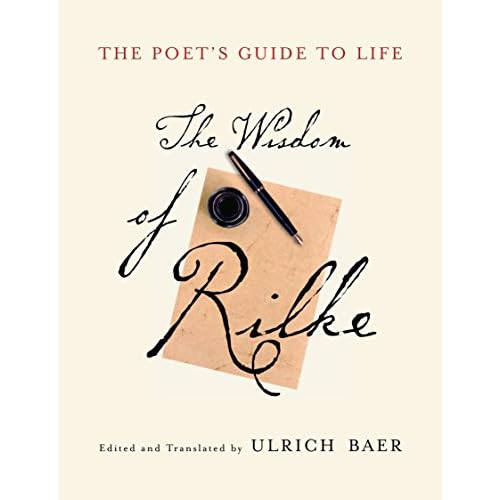

- Rainer Maria Rilke, from The Poet's Guide to Life: The Wisdom of Rilke, p. 135-136

The more I consider this question though, I find myself agreeing with Rilke's perspective. Certainly we need to be discerning and disciplined, in our lives and our art. There are a whole slew of things not worth the brief pleasures they may give us, and we need to avoid these things if we are to respect ourselves and our art. There is an opposite extreme though, and when we limit ourselves too much, avoid everything, it is another sort of disrespect for our art and ourselves. It's as though we don't want to credit ourselves as skillful players, able musicians, and complete human beings. We act as though our technical equipment is so fragile, our musical ideas so feeble, that they need constant maintenance and attention.

I'll always respect my friends who do marathon-practice sessions. Lately though, I'm of the opinion that there are times when it's better not to practice - spend the time with friends, or outdoors in nature, with poetry or literature, or maybe studying the score without your instrument to intervene. Give your imagination the opportunity to develop and keep pace with your technical command of the instrument. After all, speed and agility will never compensate for a lack of imagination. When we let our practice outstrip our lives, and the craft replace art, it only leads to those qualities of aridity, barrenness, hardness, and cowardice.

So lately I'm trying to open myself up to new things, try some courageous acts, and live a fuller life outside the practice room. I'll report on how my humble attempts go, and I hope you'll read those words of Rilke and become inspired as well!

Thursday, March 22, 2007

Rilke on life and music

Lately I've been reading a book with the rather unwieldy title The Poet's Guide to Life: The Wisdom of Rilke, edited and translated by Ulrich Baer. It's a collection of passages from Rilke's letters, which apparently comprise many more than just those few to the young poet. In fact, there are an estimated 11,000 extant letters, of which 7,000 are uncopyrighted and available to the public. Ulrich Baer notes in the introduction, "In his last will, Rilke declared every single one of his letters to be as much a part of his work as each of his many poems, and he authorized publication of the entire correspondence."

Lately I've been reading a book with the rather unwieldy title The Poet's Guide to Life: The Wisdom of Rilke, edited and translated by Ulrich Baer. It's a collection of passages from Rilke's letters, which apparently comprise many more than just those few to the young poet. In fact, there are an estimated 11,000 extant letters, of which 7,000 are uncopyrighted and available to the public. Ulrich Baer notes in the introduction, "In his last will, Rilke declared every single one of his letters to be as much a part of his work as each of his many poems, and he authorized publication of the entire correspondence."I've just begun the book, but already I've found some wonders - here are a couple of my favorites, which seem to relate to the experiences of both living and making music:

If we wish to be let in on the secrets of life, we must be mindful of two things: first, there is the great melody to which things and scents, feelings and past lives, dawns and dreams contribute in equal measure, and then there are the individual voices that complete and perfect this full chorus. And to establish the basis for a work of art, that is, for an image of life lived more deeply, lived more than life as it is lived today, and as the possibility that it remains throughout the ages, we have to adjust and set into their proper relation these two voices: the one belonging to a specific moment and the other to the group of people living in it.

Each experience has its own velocity according to which it wants to be lived if it is to be new, profound, and fruitful. To have wisdom means to discover this velocity in each individual case.

The following realization rivals in its significance a religion: that once the background melody has been discovered one is no longer baffled in one's speech and obscure in one's decisions. There is a carefree security in the simple conviction that one is part of a melody, which means that one legitimately occupies a specific space and has a specific duty toward a vast work where the least counts as much as the greatest. Not to be extraneous is the first condition for an individual to consciously and quietly come into his own.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)