It's New Year's, and this blog is now nine months old;

A few thoughts (and links), if I may be so bold:

They say success has many parents, while failure has none,

But who wants to raise a blog, when all's said and done?

Showing to everyone how poorly we edit,

Then realizing maybe no one even read it.

So I offer this poem, with just one dedication:

To those who provided this blog's inspiration!

To my nephew Isaac, born just this past spring,

His new life in Norfolk's a marvelous thing.

To Jimmy and Grandma, two losses felt deeply,

And endless The New Yorker issues bought cheaply.

To seemingly unending interstate roads,

And friendly excursions, communing with toads.

To a guy on an airplane who told me so much,

And musical hands with a sensual touch.

To Saramago and Murakami, whose books I adored,

And Crichton, and politicians I abhored.

To other Matt Hellers, whose sites may be better,

And Rainer Maria Rilke, for his wonderful letters.

To novelist Nicole Krauss, who wrote The History of Love,

And books I never read (though maybe I should've).

To wise Marcel Proust, still my favorite of all,

And to some random stranger who happened to call.

To studies on how civilizations fail;

And to Ron and Lisa, who took us to sail.

To talking with kids about musical things,

And all of the joys that an orchestra brings.

To Katrina and Wilma, I can't say we'll miss you,

Global warming's made guilt a political issue.

To Lydia's comments, a blog in themselves,

And NSA agents like sly Christmas elves.

To beautiful South Beach, with all of its wonders,

And humble Kent State, paving over its blunders.

To stuff Karen taught me on Hindemith's style,

And stuff that I learned in a grocery aisle.

To cathartic discussions while munching on challah,

And favorite composers, like Bruckner and Mahler,

And Adams, Schoenberg, Elgar, Martinu,

And while on the subject, why not Hummel too?

Dmitri, and Ludwig, and dear Humperdinck

Are harder to fit in a rhyme scheme, I think,

But still deserve mention, with Anita O'Day

And teachers, some recent and one passed away;

There's Dimoff from Cleveland, and San Francisco's Steve,

A hornist named Phil you must hear to believe,

Though for advice on auditions there may be no peer

To another from Cleveland, percussionist Tom Freer.

While few can shape time like New World's MTT;

His Don Juan was great, and his Beethoven 3.

To Knussen and Schuller, and Feltsman, and Bunch,

And Internet 2, and Marc Fest bringing lunch.

Much more could be said about music and bass,

But all of these lines are a bit of a waste

If I forget all my friends, so many in number,

Both here in Miami, and those made last summer.

For you, I hope this New Year will bring something greater,

And I'll see you all again, sooner or later.

So to 2006! and to all that's impending,

While this year, like that moving walkway, is ending.

Friday, December 30, 2005

a new year's poem

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

political dissonance

A good musical analogy can be a beautiful thing, but a bad one can drive me to insanity. I don't know how many times I've read about things "reaching a crescendo," when the writer is obviously unaware that the most quiet moment comes when the crescendo has just been reached. I guess this is one of my pet peeves. Anyway, here's David Greene in a recent column on npr.org:

Okay, I probably shouldn't get so annoyed by this. But contrapuntal lines don't have to differ in dynamic, tone, style, and certainly not in harmony. Maybe David Greene listens to a lot of Charles Ives, but when most of us hear 'counterpoint,' we think of Bach, or maybe Palestrina. Their styles allowed for a great deal of independent, contrary motion, but only within a very strict, harmonically integrated framework. The Wikipedia entry for counterpoint does have a section on dissonant counterpoint, but you have to scroll down pretty far to get to that.

Still, I hope David Greene and other political pundits won't abandon their musical analogies altogether, since it is kind of nice to imagine Bush and Cheney singing in tight Renaissance polyphony. Maybe in Maureen Dowd's next column they can do an isorhythmic motet.

Vice presidents usually sing in harmony, if not in unison, with their boss. But there are times when the No. 2 voice in the administration is most effective in counterpoint.

Vice President Dick Cheney has been especially effective in this role, often playing the "bad cop" when President Bush has chosen a softer, more sympathetic tone.

So it was again this week, when the two men defended the administration's goals and policies using highly disparate styles.- from "Cheney's Plain Talk on Presidential 'Authority'" by David Greene, Dec. 23rd, 2005, online at npr.org

Okay, I probably shouldn't get so annoyed by this. But contrapuntal lines don't have to differ in dynamic, tone, style, and certainly not in harmony. Maybe David Greene listens to a lot of Charles Ives, but when most of us hear 'counterpoint,' we think of Bach, or maybe Palestrina. Their styles allowed for a great deal of independent, contrary motion, but only within a very strict, harmonically integrated framework. The Wikipedia entry for counterpoint does have a section on dissonant counterpoint, but you have to scroll down pretty far to get to that.

Still, I hope David Greene and other political pundits won't abandon their musical analogies altogether, since it is kind of nice to imagine Bush and Cheney singing in tight Renaissance polyphony. Maybe in Maureen Dowd's next column they can do an isorhythmic motet.

Monday, December 26, 2005

Epiphany

While playing several Christmas masses this weekend at Epiphany, the enormous Catholic church shown here, I realized there are certain stories that we feel need to be told and heard again and again. And again and again and again. I can't complain so much though, since I didn't play one single Nutcracker or Messiah this year; also the church really is gorgeous, with wonderful acoustics, a devoted congregation, and a beautiful new organ.

While playing several Christmas masses this weekend at Epiphany, the enormous Catholic church shown here, I realized there are certain stories that we feel need to be told and heard again and again. And again and again and again. I can't complain so much though, since I didn't play one single Nutcracker or Messiah this year; also the church really is gorgeous, with wonderful acoustics, a devoted congregation, and a beautiful new organ.The story of my own life is admittedly not the greatest story ever told. In fact, according to Technorati, it is only the 247,530th greatest story being told on a blog at this very moment. Still though, in the spirit of this season, in which we take shiny new wrapping paper and make a great show of giving people stuff they didn't really want in the first place, I've decided to write a poem summarizing the first nine months of hella frisch, with links to some of the posts that you might have missed, whether by chance or by choice.

Sunday, December 25, 2005

light holiday reading, and existential angst

I've been reviewing some books lately in my Friendster profile. If you have bookstore gift card money to burn (or a good public library!) you might want to check some of these out:

Saturday, by Ian McEwan

You probably don't need to be a brain surgeon to navigate all the social, political, personal, and moral dilemmas faced by 21st-century people. Sometimes though, as in this novel, it might help.

You probably don't need to be a brain surgeon to navigate all the social, political, personal, and moral dilemmas faced by 21st-century people. Sometimes though, as in this novel, it might help.

Henry Perowne is a neurosurgeon (don't call him a brain surgeon, please) whose day on Saturday, February 15, 2003 begins with a chilling sight: a plane plumetting across the London sky in flames. It soon proves to be a relatively harmless malfunction, but the mood of pensive foreboding remains. It is a day marked by London's largest anti-war demonstration before the Iraq invasion, and McEwan draws a fascinating portrait of how that conflict permeates a city and an individual's consciousness.

Had I met Perowne, a grudging war supporter for humanitarian reasons, I probably would have argued fiercely against him, as his daughter does at one point in the novel. Reading this helped me to realize, though, that a sensible person could approve of military action in Iraq for rational reasons. Even now that many of the worst predictions have come true, this novel reminds of the confusion and ambivalence of that time. It rarely leaves Perowne's thoughts, even while shopping for fish or visiting his senile mother. All private thoughts and actions seem to center around this defining public event, so distant and yet so inevitable, so inescapable.

The novel explores deeply the complexities of national and personal conflict, but it is not simply a rant, or a fictionalized op-ed piece. The plot is carried along by the series of encounters and challenges facing Perowne, with a shockingly climactic finish.

An excerpt from the novel is available online: "The Diagnosis" appeared in The New Yorker last spring.

Chinese Whispers, by John Ashbery

Please don't confuse this author's name with John Ashcroft, the crooning attorney general. Ashbery is one of my favorite poets, and his writing sings with evocative turns of phrase, cliches twisted into new forms, and curious surprises. The book's title is the British name of the game known to Americans as 'Telephone,' in which the words of a story transform with each retelling.

Please don't confuse this author's name with John Ashcroft, the crooning attorney general. Ashbery is one of my favorite poets, and his writing sings with evocative turns of phrase, cliches twisted into new forms, and curious surprises. The book's title is the British name of the game known to Americans as 'Telephone,' in which the words of a story transform with each retelling.

Ashbery's poetry revels in linguistic games and puzzles, the playful intimacies suggested by "Chinese Whispers," and verses which seem to deconstruct familiar patterns of speech. Here's a bit from one called "Like Air, Almost":

I tend to read more prose, but I love how Ashbery's poetry seems to awaken the unconscious, making me feel more alive to all things, written and heard. Highly recommended for anyone who enjoys incandescent phrases and inspired nonsense.

"A Christmas Memory," "One Christmas" and "The Thanksgiving Visitor," by Truman Capote

These three holiday stories are published in the Modern Library edition shown here. Lots of people have been reading and talking about "In Cold Blood" since the film release, but the hold queue for that book was too long at my library, so I checked this out instead.

These three holiday stories are published in the Modern Library edition shown here. Lots of people have been reading and talking about "In Cold Blood" since the film release, but the hold queue for that book was too long at my library, so I checked this out instead.

Getting into the holiday spirit is a little bit difficult in warm southern climates. Still, Capote's stories are reminders that it exists wherever there are little kids:

Miss Sook Faulk is the 6-year old narrator's elderly cousin and best friend, and she is the most memorable, vivid, and lovable character in all three stories. In the first, they assemble a batch of fruitcake; the narrator journeys to New Orleans to meet his father in the second; and in the third, a savage bully visits for Thanksgiving.

Like holiday meals, the stories are filled with delights that would almost be too sweet any other time of year; their nostalgia is tinged with darkness, though, and all the cruelties, confusion, and fears of childhood. They can each be read independently, but stand together well as a collection, drawing a warm picture of friendship and holiday memories.

You can also hear "A Christmas Memory" read by Capote, courtesy of NPR and This American Life. Skip to 21:00 or so.

Saturday, by Ian McEwan

You probably don't need to be a brain surgeon to navigate all the social, political, personal, and moral dilemmas faced by 21st-century people. Sometimes though, as in this novel, it might help.

You probably don't need to be a brain surgeon to navigate all the social, political, personal, and moral dilemmas faced by 21st-century people. Sometimes though, as in this novel, it might help.Henry Perowne is a neurosurgeon (don't call him a brain surgeon, please) whose day on Saturday, February 15, 2003 begins with a chilling sight: a plane plumetting across the London sky in flames. It soon proves to be a relatively harmless malfunction, but the mood of pensive foreboding remains. It is a day marked by London's largest anti-war demonstration before the Iraq invasion, and McEwan draws a fascinating portrait of how that conflict permeates a city and an individual's consciousness.

Had I met Perowne, a grudging war supporter for humanitarian reasons, I probably would have argued fiercely against him, as his daughter does at one point in the novel. Reading this helped me to realize, though, that a sensible person could approve of military action in Iraq for rational reasons. Even now that many of the worst predictions have come true, this novel reminds of the confusion and ambivalence of that time. It rarely leaves Perowne's thoughts, even while shopping for fish or visiting his senile mother. All private thoughts and actions seem to center around this defining public event, so distant and yet so inevitable, so inescapable.

The novel explores deeply the complexities of national and personal conflict, but it is not simply a rant, or a fictionalized op-ed piece. The plot is carried along by the series of encounters and challenges facing Perowne, with a shockingly climactic finish.

An excerpt from the novel is available online: "The Diagnosis" appeared in The New Yorker last spring.

***

Chinese Whispers, by John Ashbery

Please don't confuse this author's name with John Ashcroft, the crooning attorney general. Ashbery is one of my favorite poets, and his writing sings with evocative turns of phrase, cliches twisted into new forms, and curious surprises. The book's title is the British name of the game known to Americans as 'Telephone,' in which the words of a story transform with each retelling.

Please don't confuse this author's name with John Ashcroft, the crooning attorney general. Ashbery is one of my favorite poets, and his writing sings with evocative turns of phrase, cliches twisted into new forms, and curious surprises. The book's title is the British name of the game known to Americans as 'Telephone,' in which the words of a story transform with each retelling.Ashbery's poetry revels in linguistic games and puzzles, the playful intimacies suggested by "Chinese Whispers," and verses which seem to deconstruct familiar patterns of speech. Here's a bit from one called "Like Air, Almost":

And when the post-climax happened

in soft shards, falling

this way and that,

signing the night's emeralds away,

we took it to be a sign of something.

"Must be a sign of something."

Then the wind came on, and winter with it.

"Why, weren't we just here,

five minutes ago?"

I thought I'd have another look,

but that way is all changed, and besides,

no one goes there anymore,

it's too popular.

Just one fragment

is all I ever wanted,

but I can have it, it's too much,

but its touch is for another time,

when I'm ready.

Crowd ebbs peacefully.

Hey it's all right.

I tend to read more prose, but I love how Ashbery's poetry seems to awaken the unconscious, making me feel more alive to all things, written and heard. Highly recommended for anyone who enjoys incandescent phrases and inspired nonsense.

***

"A Christmas Memory," "One Christmas" and "The Thanksgiving Visitor," by Truman Capote

These three holiday stories are published in the Modern Library edition shown here. Lots of people have been reading and talking about "In Cold Blood" since the film release, but the hold queue for that book was too long at my library, so I checked this out instead.

These three holiday stories are published in the Modern Library edition shown here. Lots of people have been reading and talking about "In Cold Blood" since the film release, but the hold queue for that book was too long at my library, so I checked this out instead.Getting into the holiday spirit is a little bit difficult in warm southern climates. Still, Capote's stories are reminders that it exists wherever there are little kids:

Snow! Until I could read myself, Sook read me many stories, and it seemed a lot of snow was in almost all of them. Drifting, dazzling fairytale flakes. It was something I dreamed about; something magical and mysterious that I wanted to see and feel and touch. Of course I never had, and neither had Sook; how could we, living in a hot place like Alabama? I don't know why she thought I would see snow in New Orleans, for New Orleans is even hotter. Never mind. She was just trying to give me courage to make the trip.

Miss Sook Faulk is the 6-year old narrator's elderly cousin and best friend, and she is the most memorable, vivid, and lovable character in all three stories. In the first, they assemble a batch of fruitcake; the narrator journeys to New Orleans to meet his father in the second; and in the third, a savage bully visits for Thanksgiving.

Like holiday meals, the stories are filled with delights that would almost be too sweet any other time of year; their nostalgia is tinged with darkness, though, and all the cruelties, confusion, and fears of childhood. They can each be read independently, but stand together well as a collection, drawing a warm picture of friendship and holiday memories.

You can also hear "A Christmas Memory" read by Capote, courtesy of NPR and This American Life. Skip to 21:00 or so.

Friday, December 23, 2005

early Christmas in Quantico

First of all I want to say that I do not in any way condone the President's policy allowing spying on American citizens. However, I do feel very sorry for the official who has to read through all my e-mail, listen to all my phone conversations, maybe even observe my day-to-day activities, like some kind of overworked national security Christmas elf. Actually, these security guys may have it worse than the elves - they don't just have to tell who's naughty and nice, they have to apprehend them, send them to a secret detention facility somewhere, maybe even build a case against some of them....

I don't get a huge amount of e-mail, but it must make for some dull reading. Also there may be some things in there which, while not necessarily incriminating, might be just bizarre enough to warrant further investigation. So as my little Christmas present to my FBI friend, I have decided to go through my e-mail records and explain some of the suspicious stuff:

Have a very happy holiday, and I hope not too many visions of scary terrorists go dancing through your head while you are all snug in your bed. BTW, I do know that the spying is being done by the NSA, not the FBI; I just thought Quantico would make for a punchier title than 'early Xmas in Ft. Meade, Maryland.'

I don't get a huge amount of e-mail, but it must make for some dull reading. Also there may be some things in there which, while not necessarily incriminating, might be just bizarre enough to warrant further investigation. So as my little Christmas present to my FBI friend, I have decided to go through my e-mail records and explain some of the suspicious stuff:

- "ANTI-SPAM BLOCKER VIRUS SPYWARE RENEW NOW!" - Ever since I bought a new computer last May, I have been getting these messages almost daily, which apparently concern some dire threat to my 'firewall.' As I don't know what that is, I have been disregarding these messages, and you should too. I am most assuredly not planning on contaminating the nation's processed meat supply.

- IMPORTANT REQUESTS FROM NIGERIAN TREASURY OFFICIALS - Usually I just ignore these, and let the $10 million fall into the hands of the Nigerian Evil Military Guerilla Brigade. Once in a while, though, I'll write back, promising my bank account info in the first paragraph, then the next 10 paragraphs will be chatty questions about Nigeria, stories about my friend who went to Haiti once etc., and I'll forget all about the bank account stuff.

- EXTENSIVE E-MAIL, PHONE, AND LIVE CONVERSATIONS ON HOW TO CHECK LARGE, UNWIELDY TRUNKS ON COMMERCIAL DOMESTIC FLIGHTS - This is a topic of great interest to all bass players, perhaps only slightly less interest than French vs. German bow or the eternal rosin quandary. None of these are of even remote interest to anyone else (except maybe tuba players).

- "ALL YOUR BASE ARE BELONG TO US" - I have no idea what this means, or how it got into my inbox. If it is some kind of secret code phrase, though, this little sleeper cell is still asleep.

Have a very happy holiday, and I hope not too many visions of scary terrorists go dancing through your head while you are all snug in your bed. BTW, I do know that the spying is being done by the NSA, not the FBI; I just thought Quantico would make for a punchier title than 'early Xmas in Ft. Meade, Maryland.'

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

zen mind, bassist's mind?

There are several poor ways of practice that you should understand. Usually when you practice zazen, you become very idealistic, and you set up an ideal or goal which you strive to attain and fulfill. But as I have often said, this is absurd. When you are idealistic, you have some gaining idea within yourself; by the time you attain your ideal or goal, your gaining idea will create another ideal. So as long as your practice is based on a gaining idea, and you practice zazen in an idealistic way, you will have no time actually to attain your ideal. Moreover, you will be sacrificing the meat of your practice. Because your attainment is always ahead, you will always be sacrificing now for some ideal in the future. You end up with nothing. This is absurd; it is not adequate practice at all. But even worse than this idealistic attitude is to practice zazen in competition with someone else. This is a poor, shabby kind of practice.Recently I've been reading Shunryu Suzuki's teachings on Buddhist meditation practice, known as 'zazen,' as an analogy to musical practice. As in meditation, musicians try and maintain an elevated state of focus, to purify ourselves of all excess thoughts and doubts, to ultimately transcend our limitations and become part of something greater than ourselves. I wonder if the analogy doesn't break down a bit here, though. My practice has always seemed to center on idealistic thinking - whether it be winning an audition or just playing a certain passage in tune!

- from "Mistakes in Practice," Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind by Shunryu Suzuki, p. 71-72

Of course, obsessing over ideals doesn't cause them to be realized. Only careful, disciplined work can do that. And I agree with Suzuki-roshi that competitive striving only results in a shabby sort of practice. The problem is finding some source of motivation, a way to pull ourselves forward without grasping at unseen goals or clawing at our competitors. As Suzuki-roshi says later in the same chapter:

So as long as you continue your practice, you are quite safe, but as it is very difficult to continue, you must find some way to encourage yourself. As it is hard to encourage yourself without becoming involved in some poor kind of practice, to continue our pure practice by yourself may be rather difficult.He goes on to write about the advantages and difficulties of having a teacher, also similar in meditation and music. Most of us at some point feel the need to find our way by ourselves, though, however useful a teacher may be. Being without a regular teacher, I find I am especially appreciative of those I do meet occasionally, as well as other outside sources of wisdom I can apply to the bass, like Suzuki-roshi's book. It is no small feat to master any sort of art, not the least of which is the art of sitting calmly and mindfully in meditation - and those who can maintain their practices with humility and dedication are particularly to be admired!

Tuesday, December 20, 2005

happy holidays with surprising swizzle sticks

Maybe it's a result of my upbringing beneath the majestic mountains and overcast skies of Tacoma, Washington. Or maybe it's the all-pervasive holiday advertising blitz at Starbucks. But whatever the reason, nothing symbolizes Christmas time for me like the Pacific Northwest. I unfortunately won't be there to visit family this year, but my Dad and step-mom Theresa were nice enough to send this lovely gift basket, full of Washington-linked food products.

Coffee and tea, smoked salmon, caramel nuts, chocolate truffles, I have no complaints with any of these things. But 'Pickled Crispy Beans'? What do these have to do with my native state? The label suggests that I 'Use Beans as a surprising swizzle stick in Bloody Mary cocktails!' Somehow that sounds more to me like something a Californian would do.

Coffee and tea, smoked salmon, caramel nuts, chocolate truffles, I have no complaints with any of these things. But 'Pickled Crispy Beans'? What do these have to do with my native state? The label suggests that I 'Use Beans as a surprising swizzle stick in Bloody Mary cocktails!' Somehow that sounds more to me like something a Californian would do.

Anyway, in honor of its transcontinental journey, I've photographed the gift basket surrounded by some made in Florida specialties, such as bananas, avocado, and grapefruit. I wasn't able to include any horrific traffic jams or fraudulent elections.

Thanks Dad and Theresa, and merry Christmas!

Coffee and tea, smoked salmon, caramel nuts, chocolate truffles, I have no complaints with any of these things. But 'Pickled Crispy Beans'? What do these have to do with my native state? The label suggests that I 'Use Beans as a surprising swizzle stick in Bloody Mary cocktails!' Somehow that sounds more to me like something a Californian would do.

Coffee and tea, smoked salmon, caramel nuts, chocolate truffles, I have no complaints with any of these things. But 'Pickled Crispy Beans'? What do these have to do with my native state? The label suggests that I 'Use Beans as a surprising swizzle stick in Bloody Mary cocktails!' Somehow that sounds more to me like something a Californian would do.Anyway, in honor of its transcontinental journey, I've photographed the gift basket surrounded by some made in Florida specialties, such as bananas, avocado, and grapefruit. I wasn't able to include any horrific traffic jams or fraudulent elections.

Thanks Dad and Theresa, and merry Christmas!

Monday, December 19, 2005

express lane psychoanalysis

There's a lot you can learn about people by the way they grocery shop, and not just what kinds of foods they like to eat. Do you choose a cart, or a basket, or start with the basket until it gets too heavy and then resort to the cart? Do you come with a carefully compiled list, or grab items from the shelves on impulse? Are you captive to the siren-song of the weekly specials, or will you buy the same stuff no matter what's on sale? How exacting are you with your produce - are you a sniffer, fondler, gentle shaker, or will you squeeze until it bruises and remove all doubt? We haven't even approached paper or plastic yet.

my pleasurable Publix: bring your id, and your ID

I went grocery shopping recently with a friend, who happens to be vegan, and was fascinated to see how our shopping styles diverged. I dithered in the canned goods, while his most lengthy deliberations were in the cereal aisle. If the grocery store is also a test of one's qualities as a friend, I suppose I failed that test - whereas he patiently watched me calculate the economics of my chickpea options, I was off somewhere in the frozen foods by the time he chose his honey bunches of whatever. We reconnected at the check-out line, though, showing that even though our styles are different, our overall grocery-shopping tempos coincide.

My mom and my step-dad, Barry, actually went to a grocery store on their first date. This is not as strange as it might sound, since they live in Las Vegas, where the grocery store is one of the few neutral, smoke-free, air-conditioned places, where you are somewhat less likely to bump into any slot machines or cocktail waitresses. And apparently they hit it off well, which is a great comfort to me, since the grocery store seems to bring out all of my mother's most bizarre and compulsive bargain-hunting proclivities. The fact that he can tolerate and even enjoy her grocery habits suggests that they'll have a long, happy life together.

I think it would be entirely possible for some computationally-gifted psychoanalyst to write an algorithm that would print out a comprehensive personality profile along with your grocery receipt. It would take into account all your grocery decisions, as well as the time it took you to make them, and maybe also your smutty tabloid periodical of choice. Of course, this is very possibly what they've been doing all along, with those 'preferred shopper' discount cards, and just keeping all the information they discover to themselves.

I'm thankful that neither of my grocery stores here in Miami have those cards, since they always seemed to bring out my wackiest paranoid tendencies. I used to wonder how carefully the store was tracking my purchases, whether they realized I hadn't bought any toilet paper in four months and were now going to raise all the prices in my hour of desperation. My common sense told me this was ridiculous, but my corporate distrust was never quite so sure.

So I would try and get friends or random strangers to switch cards with me, often while waiting in the check-out line, which would prompt their incredulous stares and sometimes they'd switch to another line. Which was okay, since then I'd get to the front that much quicker. Where I'd answer the inevitable "Paper or plastic?" with, "Neither, thanks, I brought my own bags." Others might diagnose this as obsessive eco-narcissism; I always saw it as a sign of admirable self-sufficiency.

my pleasurable Publix: bring your id, and your ID

I went grocery shopping recently with a friend, who happens to be vegan, and was fascinated to see how our shopping styles diverged. I dithered in the canned goods, while his most lengthy deliberations were in the cereal aisle. If the grocery store is also a test of one's qualities as a friend, I suppose I failed that test - whereas he patiently watched me calculate the economics of my chickpea options, I was off somewhere in the frozen foods by the time he chose his honey bunches of whatever. We reconnected at the check-out line, though, showing that even though our styles are different, our overall grocery-shopping tempos coincide.

My mom and my step-dad, Barry, actually went to a grocery store on their first date. This is not as strange as it might sound, since they live in Las Vegas, where the grocery store is one of the few neutral, smoke-free, air-conditioned places, where you are somewhat less likely to bump into any slot machines or cocktail waitresses. And apparently they hit it off well, which is a great comfort to me, since the grocery store seems to bring out all of my mother's most bizarre and compulsive bargain-hunting proclivities. The fact that he can tolerate and even enjoy her grocery habits suggests that they'll have a long, happy life together.

I think it would be entirely possible for some computationally-gifted psychoanalyst to write an algorithm that would print out a comprehensive personality profile along with your grocery receipt. It would take into account all your grocery decisions, as well as the time it took you to make them, and maybe also your smutty tabloid periodical of choice. Of course, this is very possibly what they've been doing all along, with those 'preferred shopper' discount cards, and just keeping all the information they discover to themselves.

I'm thankful that neither of my grocery stores here in Miami have those cards, since they always seemed to bring out my wackiest paranoid tendencies. I used to wonder how carefully the store was tracking my purchases, whether they realized I hadn't bought any toilet paper in four months and were now going to raise all the prices in my hour of desperation. My common sense told me this was ridiculous, but my corporate distrust was never quite so sure.

So I would try and get friends or random strangers to switch cards with me, often while waiting in the check-out line, which would prompt their incredulous stares and sometimes they'd switch to another line. Which was okay, since then I'd get to the front that much quicker. Where I'd answer the inevitable "Paper or plastic?" with, "Neither, thanks, I brought my own bags." Others might diagnose this as obsessive eco-narcissism; I always saw it as a sign of admirable self-sufficiency.

a somber note

Tragedy struck just off Miami Beach this afternoon, when a sea plane crashed just after take-off. I wasn't a witness to the disaster, but it is always a shock to find something terrible has happened so nearby. As you'd expect, the news coverage so far has been limited to speculation around the same stark facts: no survivors, no clear cause. The best articles I have come across are in the Miami Herald and the New York Times.

Sunday, December 18, 2005

a Saturday you don't want to end

I've been reading Ian McEwan's most recent novel Saturday, which takes a somewhat Joycean trip through a single day, but stays resolutely in the consciousness of one character, in the manner of Proust. I haven't finished it yet, but I wanted to share a couple of passages which especially struck me.

I've been reading Ian McEwan's most recent novel Saturday, which takes a somewhat Joycean trip through a single day, but stays resolutely in the consciousness of one character, in the manner of Proust. I haven't finished it yet, but I wanted to share a couple of passages which especially struck me.This first one comes during a hard-fought squash game pitting Henry Perowne, the novel's neurosurgeon protagonist, against his anaesthesiologist colleague Jay Strauss:

Jay's prepared to let the rallies go on while he hogs centre court and lobs to the back, drops to the front, and finds his angle shots. Perowne scampers around his opponent like a circus pony. He twists back to life balls out of the rear corners, then dashes forwards at a stretch to connect with the drop shots. The constant change of direction tires him as much as his gathering self-hatred. Why has he volunteered for, even anticipated with pleasure, this humiliation, this torture? It's at moments like these in a game that the essentials of his character are exposed: narrow, ineffectual, stupid -- and morally so. The game becomes an extended metaphor of character defect. Every error he makes is so profoundly, so irritatingly typical of himself, instantly familiar, like a signature, like a tissue scar of some deformation in a private place. As intimate and self-evident as the feel of his tongue in his mouth. Only he can go wrong in quite this way, and only he deserves to lose in just this manner. As the points fall he draws his remaining energy from a darkening pool of fury.Perowne is always forming clinical associations with events in the outer and inner worlds, but the richness of his allusions can draw the reader towards one's own associations and pathologies. This passage reminded me of how, when things go wrong, frustrations can seem to swirl out of control, making me doubt every aspect of my personality. A moment later, though, the game's momentum has turned again, and all the furious self-hatred is forgotten.

This other passage describes watching Perowne's blues guitarist son Theo play:

No longer tired, Henry comes away from the wall where he's been leaning, and walks into the middle of the dark auditorium, towards the great engine of sound. He lets it engulf him. There are these rare moments when musicians together touch something sweeter than they've ever found before in rehearsals or performance, beyond the merely collaborative or technically proficient, when their expression becomes as easy and graceful as friendship or love. This is when they give us a glimpse of what we might be, of our best selves, and of an impossible world in which you give everything you have to others, but lose nothing of yourself. Out in the real world there exist detailed plans, visionary projects for peaceable realms, all conflicts resolved, happiness for everyone, for ever -- mirages for which people are prepared to die and kill. Christ's kingdom on earth, the workers' paradise, the ideal Islamic state. But only in music, and only on rare occasions, does the curtain actually lift on this dream of community, and it's tantalisingly conjured, before fading away with the last notes.Of course McEwan will bias a lot of musician readers in his favor, with descriptions like that! Proust and Joyce both wrote equally eloquent praise of music, though, and they were no worse for it.

I will probably have more to say about Saturday once I finish it. In the meantime you can read "The Diagnosis," an excerpt which appeared in The New Yorker online, or visit McEwan's own website. It is a novel of our time, set in the winter of 2003 and containing meditations on the coming Iraq war, the battle between religious fundamentalism and consumer culture, and the peculiar situation of affluent first-world people enjoying advantages greater than at any other time in history, while the world edges towards a new dark age. I think much of the novel is timeless though, and will be recognized and appreciated by people in whatever dystopic ages might follow ours.

Saturday, December 17, 2005

Shostakovich's savage Seventh

People often say about a film that it has to be experienced in a real movie theater, with the massive screen, the pounding speakers, the gasping crowd, to be properly appreciated. I think of Shostakovich's 7th Symphony the same way - I never much liked it until I got to play it and experience the epic sweep of the thing. It can be long-winded, unwieldy, and sometimes comically banal - Bartok famously mocked its first movement march in his Concerto for Orchestra - yet it all fits together very powerfully in a concert hall, where you can't turn away from its triteness or its pathos.

People often say about a film that it has to be experienced in a real movie theater, with the massive screen, the pounding speakers, the gasping crowd, to be properly appreciated. I think of Shostakovich's 7th Symphony the same way - I never much liked it until I got to play it and experience the epic sweep of the thing. It can be long-winded, unwieldy, and sometimes comically banal - Bartok famously mocked its first movement march in his Concerto for Orchestra - yet it all fits together very powerfully in a concert hall, where you can't turn away from its triteness or its pathos.Before our first performance last night, conductor Michael Tilson Thomas described meeting Shostakovich on a visit from Soviet artists to Southern California. Even in that sunny clime, MTT said, Shostakovich seemed perpetually under a cloud, a distant, haunted man whose suspicious gaze wasn't softened by American teenagers requesting autographs. I suppose it's still a miracle to me, no matter how often I see it performed, that a few pages of dots and dashes, abstract symbols, can take flight and convey something powerful and unspeakable 60 years later.

MTT described Shostakovich as a composer whose natural inclination was towards the kind of avant-grade modernism being written in Paris, spare and ironic in the manner of Satie or early Prokofiev. He was a citizen of an authoritarian regime, though, and he was compelled to write grand symphonies in the Austro-German tradition - ironically, those same nations whose army threatened Leningrad at the time Shostakovich wrote his Seventh. Shostakovich was a master of irony, and his first movement is interrupted by a long march, the passage that inspired Bartok's scorn and many others' confusion. It begins as merely an asinine, repetitive tune, accompanied by snare drum, but gradually builds to a terrifying climax, the same insidious melody now rising over shrieks and moans - like an evil psycopathic cousin to Bolero, never losing its maniacal grin.

I think for a long time I shared Bartok's derision for this march, and for the symphony as a whole. Its whole history seemed to suggest the composer selling out, quickly throwing together a patriotic anthem, intended to build up morale and excite foreign support for the Soviet cause. It seems to have done the trick: as the seige of Leningrad was halted, the symphony was an immediate popular success around the world.

With Shostakovich, though, you're never quite sure if there is another layer you're missing. Listening to it now, I hear the message that not only is war cruel and ugly, but the patriotic faces we put on in response are just as horrifying, and disfiguring. Along with the morbid, political themes, though, there is music so graceful, so innocent and nostalgic for beauty and purer pursuits - like the third movement waltz that inspired MTT to do an ice-skating demonstration on the podium during rehearsal. Maybe there's a whole other level I'm still just missing.

I wrote a little review for my Friendster profile as well:

Why did Shostakovich trivialize his 7th Symphony with one of the most idiotic themes ever written? Written during Leningrad's resistance to the Nazi invasion in 1942, the symphony contains some of Shostakovich's most rapturous, profound music - and a march so dumb that even the greatest orchestras sound silly playing it.

I think of it as the atomic bomb of thematic motives, a tune that stays in your head longer than the half-lives of most radioactive isotopes. Maybe the idea was not only to defeat Hitler's army, but send them back to Berlin humming a melody that would make their friends want to kill them as well.

Our orchestra will play two performances of the symphony this weekend, under the direction of Michael Tilson Thomas. Take cover, this is music at its most brutal and senseless!

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Dept. of Orchestrational Exaggeration

Evidently back in the 1940's The New Yorker's fact checking was not up to its present high standards, or else the Mr. Spitalny quoted in the piece posted yesterday was not much of a score reader at all. Shostakovich's Seventh Symphony begins with the full string section, marked forte, not with a single quiet snare drum as the quote implied. Later in the first movement, a long march does begin with a single snare drum. And all hell does break loose at the end.

I'm guilty of some exaggeration of my own. Our orchestra's parts this week aren't from the 1940's as I implied, the semi-legible script on my photocopy only suggests an antiquated era. The performance parts themselves (or scores, if you like) are brand new and carefully corrected by our orchestra librarians, Martha Levine and Chris Blackmon. It's a good thing I don't have to be so fastidious (and can occasionally sneak in later and edit!) or else every post I write would be followed by a longer list of corrections!

I'm guilty of some exaggeration of my own. Our orchestra's parts this week aren't from the 1940's as I implied, the semi-legible script on my photocopy only suggests an antiquated era. The performance parts themselves (or scores, if you like) are brand new and carefully corrected by our orchestra librarians, Martha Levine and Chris Blackmon. It's a good thing I don't have to be so fastidious (and can occasionally sneak in later and edit!) or else every post I write would be followed by a longer list of corrections!

Monday, December 12, 2005

next weekend's Shostakovich: "We can hardly wait"

This is from a Talk of the Town piece that appeared in The New Yorker magazine of July 18, 1942, the week that Shostakovich's 'Leningrad' Symphony no. 7 was given its North American premiere by Toscanini and the NBC Symphony. (Mr. Belviso is Thomas Belviso, the orchestra's librarian):

At the time of our call, Mr. Belviso happened to have in his office an extra score of the first violin part. We opened its green covers with due reverence, noting that it was thirty-five pages long and seemed to be CNMPOHNR No. 7. Anyway, it was Op. 60, and the tempo markings of the four movements were in the orthodox Italian: allegretto, moderato poco allegretto, adagio, and allegro non troppo. Mr. H. Leopold Spitalny, the N.B.C.'s Director of Orchestra Personnel, happened in, and we asked him if he could describe the symphony for us, since he had read it. "Well," he said, "it starts with deceptive softness -- a roll of a single snare drum. But it ends, ninety minutes later, with all hell breaking loose." We can hardly wait.Interestingly, due to the intricacies of rental agreements and copyright law, we seem to be playing on those same green parts, or something very nearly as old. You can visit the New World Symphony website to learn more.

- The New Yorker, June 18, 1942, p. 9; available in The Complete New Yorker

Labels:

New World,

Shostakovich,

The New Yorker,

upcoming concerts

Sunday, December 11, 2005

feed the frisch

I recently noticed my Gmail account is now operating little web clips above my inbox, and asking me if I want to replace the boring, generic default clips with those of my friends. That's right, I have a friend who has an 'RSS feed' (two, actually): Joe Lewis of SanBeiJi.com.

I now have one too, so if you are feeling intrepid, you can get little hella frisch updates while checking your e-mail. Just go to 'Settings' on the top of the Gmail page, click the tab for 'Web Clips,' and enter the following gobbledygook in the box under 'Search by topic or url:'

http://feeds.feedburner.com/HellaFrisch

I promise this won't allow me to read your e-mail or spy on your internet predilections. It may just add a little hella frisch to your day, though, without having to read the whole thing.

Happy feeding!

I now have one too, so if you are feeling intrepid, you can get little hella frisch updates while checking your e-mail. Just go to 'Settings' on the top of the Gmail page, click the tab for 'Web Clips,' and enter the following gobbledygook in the box under 'Search by topic or url:'

http://feeds.feedburner.com/HellaFrisch

I promise this won't allow me to read your e-mail or spy on your internet predilections. It may just add a little hella frisch to your day, though, without having to read the whole thing.

Happy feeding!

Saturday, December 10, 2005

remembering a legendary teacher

I'm still collecting my thoughts today after learning of the passing of Homer Mensch, a great bassist and teacher. Mr. Mensch is probably best known as the man who recorded those two famous repeated notes in the movie soundtrack for "Jaws." It seems strange to remember him that way, though, since to me he represented everything that was serious, noble, and uncompromising in music. I was lucky enough to study with him at Juilliard, though our relationship unfortunately didn't last very long.

I'm still collecting my thoughts today after learning of the passing of Homer Mensch, a great bassist and teacher. Mr. Mensch is probably best known as the man who recorded those two famous repeated notes in the movie soundtrack for "Jaws." It seems strange to remember him that way, though, since to me he represented everything that was serious, noble, and uncompromising in music. I was lucky enough to study with him at Juilliard, though our relationship unfortunately didn't last very long.I've heard it said that at a place like Juilliard, the studio teachers are treated as gods. Mr. Mensch certainly was that to me. It seemed a lot to hope that he would even remember my name between lessons, much less form a personal relationship with me. I remember getting frantically anxious every time I called to arrange a lesson, then stuttering, "This is Matt Heller, your bass student from Columbia." I was in a tiny "dual exchange" program that registered me as a full-time Columbia student but let me take lessons and studio class at Juilliard.

It's difficult to express the kind of authority and respect that Mr. Mensch commanded. His comments really did seem to carry the weight of divine pronouncements, which was perhaps increased by the strange passive language he would use. The highest compliment I ever received from him was "That plays well," and that was a rare event - as you can imagine, most of what I brought to my lessons did not "play well" at all! He would sit behind his desk, dispensing corrected bowings and fingerings, and his criticism was almost always delivered coolly and dispassionately. It was all the more devastating that way.

As in most student-teacher relationships, I never spent more than two or three hours a week with Mr. Mensch, both in lessons and studio class. Those few hours telescoped mightily into the rest of my life, though, as his comments and suggestions echoed through many hours in the practice room. Where a strong bond exists, a teacher can profoundly impact every aspect of the student's development as a musician - the approaches to problem-solving, the interpretive choices, the ear for a particular tone quality. I don't think I had enough time to really internalize much of Mr. Mensch's teaching, but I still hear his voice occasionally, and still do some of the drills he prescribed to his students. There was one in particular, a slow bow drill which was intended to last half an hour, and which I continued doing daily years after I left his studio. It was like a morning meditation, exploring the limits of sustained, pure tone, and it was the closest thing to spiritual transformation that I had as a secular 18-year old.

I knew after my first lesson with Mr. Mensch, as a matter of fact, that I didn't want to stay in the Columbia program. What made me leave was the realization that no matter how hard I tried, I would never be able to live up to Mr. Mensch's expectations. More than the long subway commutes, more even than the full academic course load, it was the social atmosphere at Columbia, my dorm-mates' endless inane conversations and all-night video game marathons that kept me up when I needed to practice the next morning. I told Mr. Mensch my concerns, and actually persuaded him to write a letter to the Juilliard dean, requesting that I be permitted to transfer to Juilliard full-time and to leave Columbia. With such a divine intervention, I thought, my petition could never be denied - it was, though, and so I ended up transferring to study with another Homer Mensch student, Donald Palma at the New England Conservatory.

My last lesson with Mr. Mensch really stung, and it's probably the reason I fell out of touch with him so completely. Where before he had held back from really harsh criticism, leaving seemed to give him license to say all the most devastating things he could, some of which have stayed with me ever since, like his description of my sound as "brittle." I left that lesson in tears, angry and bewildered and wildly hopeless, as if I'd just been thrown out of Valhalla. I saw him once more afterwards, when I played in Jaime Laredo's New York String Orchestra in Carnegie Hall, and I was chosen to lead the section - he said something vaguely positive about my leadership, which I took as a small vindication. Still, I felt like I left Mr. Mensch's studio under a cloud, crippled by his rebuke, and I found myself frequently explaining apologetically to people who saw my resume why I had left Juilliard after just one semester.

Thinking back now, it seems strange to realize that I left because I wanted to earn Mr. Mensch's praise. I would tell people that he was part of the reason I left - he was too old, he couldn't demonstrate technique in the way I needed. I don't think I really believed that for a moment, though. Being around this legendary bassist, experiencing how demanding a musician's ear, how probing his mind could be, made me aspire to become all that, more than I ever had before. And as is often the case with teachers, parents, or gods, I suppose, we want so badly to please them, we hunger so deeply for their respect, that we end up leaving them and, in many cases, we lose them forever.

I was amused to find a little piece about Homer Mensch from the New York Times online, dated March 17, 1984 and entitled "Stringed Subway Rider." There is also a nice recent interview (as well as the photograph posted above) on the Juilliard School's website. Several of the other bass players here at the New World Symphony, and hundreds more scattered around the world, also studied with Mr. Mensch and will miss him deeply.

Friday, December 09, 2005

changing a climate of apathy

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote a series of insightful and moving articles on climate change last summer, to be published early next year as Field Notes from a Catastrophe. As world leaders meet in Montreal for another round of negotiations, she underscores the gravity of the situation in "Global Warning," a short comment published in this week's New Yorker.

Here is how Kolbert summarizes the current policy:

The President's call for voluntary action, while displaying a heartwarming faith in the altruism of the American people, is not the action that is needed. Americans are as good and nature-loving as any people, but few of us will change our behaviors until the demands of our consciences dovetail with our economic self-interests. This is why governmental regulations, in conjunction with international agreements, are so necessary in solving this problem - in the words of the Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin, "To the reticent nations, including the United States, I say this: There is such a thing as a global conscience. And now is the time to listen to it."

Unfortunately, though, our government is not listening - and by walking out of the talks today, they have continued in the apathetic hubris that, as Kolbert says, amounts to a rush towards catastrophe. Long after names like Harriet Miers, Valerie Plame, Michael Brown, and Abu Ghraib have faded into history's trivia, this administration's policy of inaction may be remembered as its great failing.

After reading Kolbert's comment, I found myself wishing that, rather than Montreal, the conference could be held on one of the tiny Pacific islands she describes, preferably one in imminent danger of flooding and destruction. That way the negotiators would be forced to come to an agreement before the water rushed in and drowned them. Of course, that might imperil the lives of a lot of innocent officials - still, walking out is a lot harder when you're waist-deep in water!

By the way, if anyone knows why this article was accompanied by a drawing of George W. playing the violin while wearing a toga, please let me know. I confess that The New Yorker's sense of humor is sometimes beyond me.

Here is how Kolbert summarizes the current policy:

When the Bush Administration’s policy on climate change was first articulated by the President, in early 2002, critics described it as a “total charade,” a characterization that, if anything, has come to seem too generous. Stripped down to its essentials, the Administration’s position is that global warming is a problem that either will solve itself or won’t. The White House has consistently opposed taxes or regulations or mandatory caps to reduce, or even just stabilize, greenhouse-gas emissions, advocating instead a purely voluntary approach, under which companies and individuals can choose to cut their CO2 production—that is, if they feel like it.Now, I can very easily tell myself that I'm going to wake up at 5:30 tomorrow morning. Unless I set my alarm and get to bed early tonight, though, it's very unlikely to happen. In the same way, reducing CO2 emissions is an achievable goal, but we won't achieve it unless we take action now.

The President's call for voluntary action, while displaying a heartwarming faith in the altruism of the American people, is not the action that is needed. Americans are as good and nature-loving as any people, but few of us will change our behaviors until the demands of our consciences dovetail with our economic self-interests. This is why governmental regulations, in conjunction with international agreements, are so necessary in solving this problem - in the words of the Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin, "To the reticent nations, including the United States, I say this: There is such a thing as a global conscience. And now is the time to listen to it."

Unfortunately, though, our government is not listening - and by walking out of the talks today, they have continued in the apathetic hubris that, as Kolbert says, amounts to a rush towards catastrophe. Long after names like Harriet Miers, Valerie Plame, Michael Brown, and Abu Ghraib have faded into history's trivia, this administration's policy of inaction may be remembered as its great failing.

After reading Kolbert's comment, I found myself wishing that, rather than Montreal, the conference could be held on one of the tiny Pacific islands she describes, preferably one in imminent danger of flooding and destruction. That way the negotiators would be forced to come to an agreement before the water rushed in and drowned them. Of course, that might imperil the lives of a lot of innocent officials - still, walking out is a lot harder when you're waist-deep in water!

By the way, if anyone knows why this article was accompanied by a drawing of George W. playing the violin while wearing a toga, please let me know. I confess that The New Yorker's sense of humor is sometimes beyond me.

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

deep philosophy and concussions

This past weekend The New York Times Magazine featured a long article by Michael Lewis, "Coach Leach Goes Deep, Very Deep." I don't even like football, but I'll read anything by Michael Lewis, and this article was definitely well worth reading. Lewis specializes in people approaching familiar problems in wildly novel ways, and their successes not only inspire but provide insights into other fields.

Here's something about a problem familiar in our field, tempo:

So many times in my own practice I've found it equally dangerous to pat myself on the back or kick myself in the butt - they both draw me out of focus. The article is quite long, but it's filled with little gems like that.

Here's something about a problem familiar in our field, tempo:

[Leach] had been harping on tempo all week: he thinks the team that wins is the team that moves fastest, and the team that moves fastest is the team that wants to. He believes that both failure and success slow players down, unless they will themselves not to slow down. "When they fail, they become frustrated," he says. "When they have success, they want to become the thinking-man's football team. They start having these quilting bees, these little bridge parties at the line of scrimmage."

So many times in my own practice I've found it equally dangerous to pat myself on the back or kick myself in the butt - they both draw me out of focus. The article is quite long, but it's filled with little gems like that.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

the ascetic sensualist

My first summer at the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, we had a bass coach named Wolfgang Güttler, a long-haired bear of a man, born in Transylvania and seemingly possessed by some sort of demonic force. I'll never forget the time while playing Scheherezade's storm scene he decided the bass section wasn't swaying enough to the music, and so he grabbed me and began throttling me from side to side, almost capsizing me off my stool, instrument and all. Another time he tried to teach a Chinese bassist named Li to play with more dance-like character by waltzing around the stage with him, as the rest of us played Blue Danube and watched in disbelief.

After a marathon 6-hour sectional with Güttler, we would often go back to the castle (the orchestra lived in a castle - a small one, with a bar) and listen to bass recordings and drink red wine. Güttler had brought several of his own recordings, of Bottesini solo pieces as well as a very avant-garde group he formed called Trio Basso. Other people also had interesting recordings, and not just bass solo recordings, but Güttler would dominate the proceedings by repeatedly insisting, "Very nice! Now maybe we hear again the Riehm, how it sounds after this..." It was never enough to hear his recordings just once, and every other recording seemed to inspire him to want to hear something of his again.

At the time, I thought this was just more evidence of Güttler's crazed megalomania, though I've wondered about it a lot since then. I think we musicians are all very sensual people, in the pure sense of the term (I'll leave the impure sense to Blair Tindall et al.!) Like wine connoiseurs, we're rarely satisfied by one taste of music - we need to try a slower sip, or after a nice curry, or maybe with dessert? The experience of sound fills everyone with delight, but it also fills us with unquenchable curiosity: but how would that sound if...?

And when you think about it, who but a sensualist could spend hours alone in a practice room, deeply absorbed in questions like, "But how would this feel if it were slower? Faster? Maybe slower but with more forward movement...and what about using the second finger rather than the third?" I notice my musician blogger idol Jeremy Denk has a recent post entitled "How to Climax," which makes me wonder in what other profession can you occupy hours of meditation and study with such a question? Certainly not tollbooth collectors, mail delivery people, pet groomers... probably very few professions, and most of them illegal.

Of course, I prefer not to think too carefully about the sensualist leanings of my first bass teacher, the grandmotherly old lady with the gold star chart who loved to use the word 'discombobulated.' Or those of Wolfgang Güttler, or most musicians I can think of, for that matter. Still, sitting here comparing Bylsma's and Wispelwey's Bach recordings, I'm reminded of that "Maybe we hear again, how it sounds after this?" And it makes me think that within each of our ascetic practice room existences, there lives a decadent sensualist, indulging shamelessly in the endless permutations of sound, where hopefully we can't do very much damage.

After a marathon 6-hour sectional with Güttler, we would often go back to the castle (the orchestra lived in a castle - a small one, with a bar) and listen to bass recordings and drink red wine. Güttler had brought several of his own recordings, of Bottesini solo pieces as well as a very avant-garde group he formed called Trio Basso. Other people also had interesting recordings, and not just bass solo recordings, but Güttler would dominate the proceedings by repeatedly insisting, "Very nice! Now maybe we hear again the Riehm, how it sounds after this..." It was never enough to hear his recordings just once, and every other recording seemed to inspire him to want to hear something of his again.

At the time, I thought this was just more evidence of Güttler's crazed megalomania, though I've wondered about it a lot since then. I think we musicians are all very sensual people, in the pure sense of the term (I'll leave the impure sense to Blair Tindall et al.!) Like wine connoiseurs, we're rarely satisfied by one taste of music - we need to try a slower sip, or after a nice curry, or maybe with dessert? The experience of sound fills everyone with delight, but it also fills us with unquenchable curiosity: but how would that sound if...?

And when you think about it, who but a sensualist could spend hours alone in a practice room, deeply absorbed in questions like, "But how would this feel if it were slower? Faster? Maybe slower but with more forward movement...and what about using the second finger rather than the third?" I notice my musician blogger idol Jeremy Denk has a recent post entitled "How to Climax," which makes me wonder in what other profession can you occupy hours of meditation and study with such a question? Certainly not tollbooth collectors, mail delivery people, pet groomers... probably very few professions, and most of them illegal.

Of course, I prefer not to think too carefully about the sensualist leanings of my first bass teacher, the grandmotherly old lady with the gold star chart who loved to use the word 'discombobulated.' Or those of Wolfgang Güttler, or most musicians I can think of, for that matter. Still, sitting here comparing Bylsma's and Wispelwey's Bach recordings, I'm reminded of that "Maybe we hear again, how it sounds after this?" And it makes me think that within each of our ascetic practice room existences, there lives a decadent sensualist, indulging shamelessly in the endless permutations of sound, where hopefully we can't do very much damage.

Monday, December 05, 2005

Haimovitz's Goulash

NPR's Weekend Edition Sunday featured an interview yesterday with cellist Matt Haimovitz, one of the most innovative performers today. In Liane Hansen's introduction, she mentions Haimovitz touring punk rock clubs with "Bach's solo cello concertos." Maybe she spent too much time studying for the Sunday puzzle this week. She does much better in the actual interview, and Haimovitz has interesting things to say about Rumanian folk music, Led Zeppelin's Turkish connection, and his own passion to connect with people through music.

While on the subject of things cellistic, I have to rave a little bit about a performance I heard yesterday of Schubert's Cello Quintet in C major. It was part of the New World Symphony's chamber music series, and this particular concert was directed by cellist Laurence Lesser. Just thinking now about that second theme in the first movement makes my heart start to melt and go all gooey inside - in a good way. The other pieces on the program, a Boccherini cello quintet in F minor and George Crumb's An Idyll for the Misbegotten, were also very compellingly played.

While on the subject of things cellistic, I have to rave a little bit about a performance I heard yesterday of Schubert's Cello Quintet in C major. It was part of the New World Symphony's chamber music series, and this particular concert was directed by cellist Laurence Lesser. Just thinking now about that second theme in the first movement makes my heart start to melt and go all gooey inside - in a good way. The other pieces on the program, a Boccherini cello quintet in F minor and George Crumb's An Idyll for the Misbegotten, were also very compellingly played.

Sunday, December 04, 2005

but who will take on Amazoogle?

When I was 14 and people would ask me if I'd chosen a college major, I would tell them: "Prophecy." I was sort of in a Nostradamus phase at the time, and I thought it would be awfully cool to come up with cryptic sayings which no one could understand, but which came true centuries later.

I never did get my prophecy degree, but I'll use that childhood interest as an excuse to comment on "Epic 2014," a movie about how the news media industry might look in 9 years or so. It's also worth hearing Brook Gladstone's On the Media interview with Matt Thompson, the movie's creator and narrator.

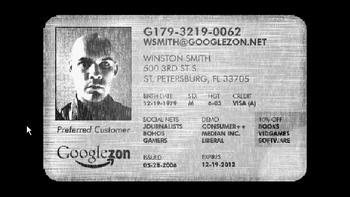

Thompson breaks a cardinal rule of Prophecy, and makes up specific names and dates rather than the vague signifiers perfected by Nostradamus. Still, it's an intriguing future - Google has merged with Amazon, to form "Googlezon," and Microsoft and Friendster have combined and perfected "NewsBotster," a service that creates an individual news outlet for every single person based on their preferences and those of their social networks. Googlezon one-ups them with "EPIC," an algorithm which mines all the content created everywhere and pieces it into news stories written entirely by robots. The clash of media titans culminates in the Supreme Court case of The New York Times vs. Googlezon, with the Times making a last stand to protect all of our personal data streams.

Probably very little of the nomination hearings for Samuel Alito will focus on how he would rule in The Times vs. Googlezon, but it's still an interesting future to ponder. It seems like a long road to a feudal information economy ruled by the all-powerful search engine overlord; the world's people transformed into information-gathering serfs. Then again, I seem to be traipsing merrily down that road right now, blogging away while surrendering my rights to private, unobserved thought.

Probably very little of the nomination hearings for Samuel Alito will focus on how he would rule in The Times vs. Googlezon, but it's still an interesting future to ponder. It seems like a long road to a feudal information economy ruled by the all-powerful search engine overlord; the world's people transformed into information-gathering serfs. Then again, I seem to be traipsing merrily down that road right now, blogging away while surrendering my rights to private, unobserved thought.

More unimaginable to me is the magical algorithm that can render all those thoughts into a coherent, satisfying, and individualized product. You can have access to all the data in the world (and by 2014 Google very well might have), but it still won't give you the ability to sort, analyze, and present that data in a convincing way. Those tasks, for better or for worse, are what we ask of our news media. If there were a way to just pick out a bunch of elements popular among a certain demographic, reconstitute them, and repackage the result as the hottest new thing, some Hollywood film studio would have figured it out long ago. In reality, the qualities that make a good film, a good book, or good journalism are much more elusive, much more mysterious, and much too complicated for any smart robot algorithm (even Google's) to figure out.

Of course, if I'm wrong about all of this, you can blame my lack of a full prophetic education.

I never did get my prophecy degree, but I'll use that childhood interest as an excuse to comment on "Epic 2014," a movie about how the news media industry might look in 9 years or so. It's also worth hearing Brook Gladstone's On the Media interview with Matt Thompson, the movie's creator and narrator.

Thompson breaks a cardinal rule of Prophecy, and makes up specific names and dates rather than the vague signifiers perfected by Nostradamus. Still, it's an intriguing future - Google has merged with Amazon, to form "Googlezon," and Microsoft and Friendster have combined and perfected "NewsBotster," a service that creates an individual news outlet for every single person based on their preferences and those of their social networks. Googlezon one-ups them with "EPIC," an algorithm which mines all the content created everywhere and pieces it into news stories written entirely by robots. The clash of media titans culminates in the Supreme Court case of The New York Times vs. Googlezon, with the Times making a last stand to protect all of our personal data streams.

Probably very little of the nomination hearings for Samuel Alito will focus on how he would rule in The Times vs. Googlezon, but it's still an interesting future to ponder. It seems like a long road to a feudal information economy ruled by the all-powerful search engine overlord; the world's people transformed into information-gathering serfs. Then again, I seem to be traipsing merrily down that road right now, blogging away while surrendering my rights to private, unobserved thought.

Probably very little of the nomination hearings for Samuel Alito will focus on how he would rule in The Times vs. Googlezon, but it's still an interesting future to ponder. It seems like a long road to a feudal information economy ruled by the all-powerful search engine overlord; the world's people transformed into information-gathering serfs. Then again, I seem to be traipsing merrily down that road right now, blogging away while surrendering my rights to private, unobserved thought.More unimaginable to me is the magical algorithm that can render all those thoughts into a coherent, satisfying, and individualized product. You can have access to all the data in the world (and by 2014 Google very well might have), but it still won't give you the ability to sort, analyze, and present that data in a convincing way. Those tasks, for better or for worse, are what we ask of our news media. If there were a way to just pick out a bunch of elements popular among a certain demographic, reconstitute them, and repackage the result as the hottest new thing, some Hollywood film studio would have figured it out long ago. In reality, the qualities that make a good film, a good book, or good journalism are much more elusive, much more mysterious, and much too complicated for any smart robot algorithm (even Google's) to figure out.

Of course, if I'm wrong about all of this, you can blame my lack of a full prophetic education.

Friday, December 02, 2005

confessions on a yoga mat

"The Joffrey is just so much central casting," said Evergreen, apropos of nothing. As a vacuum cleaner can start to pull up the actual thread of a carpet, her brains had been sucked dry by too much yoga. No one paid much attention to her.Yoga is ridiculously ubiquitous here in Miami. Jogging down South Beach in the morning, it is sometimes difficult to avoid tripping over people in plow pose (that's halasana for all you initiates). We probably have more yogis per capita than almost anywhere in the nation; and just as in Seattle you can get an espresso at the gas station or the laundromat, here you find yoga classes springing up spontaneously wherever there is a flat surface, in hotels and cosmetics stores and my jogging path on the beach.

- from "Agnes of Iowa" by Lorrie Moore, Birds of America p. 82

With so many options, though, I decided that I would resist the corporatization of yoga, all those slick operations peddling inner peace in convenient 10-class packages. It's all very well to give a corporation control over radio stations and the human genetic code, my thinking went, but once they start deciding how I inhale and exhale during my sun salutations, now they've gone too far! So rather than join the multitudes at Crunch or Bikram or the other popular yoga studios, I went in the direction of the local mom-and-pop yoga shop.

My yoga teachers last year, Garth and Bianca, literally are a mom and pop, though I doubt they would advertise themselves as such. I met Garth at the local headquarters of the Kerry for President campaign last fall, and he gave me his address and told me that he and his wife would be teaching yoga classes in their living room, twice a week in the evenings. I didn't head over there until late November, when my glumness over Kerry's defeat was beginning to wear off.

Garth and Bianca have a pleasant house in Miami Shores, with Bianca's glorious abstract paintings on the walls and their young son Tristan running around and gurgling merrily. Both are excellent teachers in the Iyengar and Ashtanga traditions of yoga, a quite intense and demanding form. Garth would put some Anita O'Day or Ravi Shankar on their fantastic stereo, and during savasana the two cats would lick my fingers while I sprawled out in peaceful exhaustion.

Often I would stay long after class, talking about music or philosophy or the evils of the Bush administration, or countless other more bizarre subjects. These are two of the most interesting people I've ever known - Garth is a retired ballet dancer from Brooklyn, and Bianca is an artist from Germany, and they met at a moonlight drum circle on Miami Beach. They both practice and teach yoga out of their devotion to the art, not for financial profit, but at some point they decided it was not worth holding classes any more. There was a massive road construction project on US-1 which made the trip to Miami Shores a serious threat to anyone's inner peace - since I was regularly the only student willing to brave the traffic, Bianca told me last spring that they were going to suspend their classes until some undetermined future date.

This was sad for me, but I was able to muddle along for a while on my own. I have the primary series pretty well down, all the sun salutations and stuff - my twin brother Dan is actually a part-time yoga teacher, and I can always try and tap into his knowledge telepathically (or by phone) if a yoga crisis should arise. At some point this fall, though, I decided I was getting into a yoga rut, and I should get back to taking classes again.

So I called another yoga friend, Luna - she and her husband Kello also recently became parents, with the birth of their son Aloe this past summer, and also have a home yoga studio. During Luna's pregnancy last spring, I would occasionally go over to their apartment on Jefferson Ave. in Miami Beach and Kello would guide me through postures, though I was again invariably the only one there. He is a good instructor, though I was occasionally disconcerted by his repeated demands that I contract my anal sphincter in order to engage the mula bandha. One of the great things about yoga, though, is that when you don't get so self-conscious, you find you can learn profound things by listening deeply to a large, blissful Jamaican man with dreadlocks named Kello.